‘She’s doing it again! Make her stop, Papa! Make her stop!’

The car swerves off the road, shuddering to a halt. The driver swivels round in his seat.

His six year-old daughter stares at him, sobbing. In her left hand she holds an ice-cream cone. Two-thirds eaten, the remaining third is melting through her fingers, dripping down onto her dress, her bare legs, the seat and the floor.

*

Dorota Batz is renowned in psychiatric circles as the world’s first, and to date only, recorded endophobe. Her diagnosis, at the age of twenty-seven by my own hands, followed years of misguided psychological enquiry by my peers which produced well-meaning but far-fetched interpretations of chronophobia, gerontophobia, sociophobia and thanatophobia, among others.

It was April when Dorota’s mother phoned my office and made an appointment for her daughter. ‘Mild psychiatric disorder’, my secretary noted.

A few words about me might help. Doctorate in Clinical Psychology from Humboldt-Universität Berlin, a board-certified cognitive therapist affiliated with Lausanne University, I treat a wide variety of anxiety-producing conditions such as life adjustment issues, relationship difficulties and mood disorders. My patients include abuse survivors, addiction recoverees, bullied children, dementia sufferers, civil servants, members of parliament and captains of industry. I play the bassoon.

Affable and erudite, Dorota told me on that first visit how her independent spirit was to blame for her mother getting it into her head that her daughter was psychologically disturbed. ‘I play along with it to humour her,’ she said. ‘It seems to give her life meaning, this mad quest to ‘cure’ me.’

‘Interesting,’ I said. ‘So there’s actually nothing the matter with you at all?’

‘I’ll let you be the judge of that,’ said Dorota.

‘Tell me about your background,’ I asked.

She was the younger of two sisters. Her father, a wealthy industrialist, had been absent abroad for much of her childhood.

‘What early memories do you have of him?’

When Dorota was tucked up in bed, her father reading a bedtime story, she would beg him to stop. ‘Don’t you want to know what happens?’ her father would ask. ‘No!’ pleaded the girl. ‘Stop!’

‘I see,’ I said.

She took a sip of water, glanced at the clock on my wall, and frowned.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said, ‘we have plenty of time.’

‘I’d like to go now,’ she said, getting to her feet and pulling on her coat.

‘That’s fine,’ I said. ‘It’s been very nice meeting you.’

She shook my hand, smiling awkwardly. When I opened the door, she bolted.

I peered out my window to catch a glimpse of her. She emerged out onto the pavement, lit a cigarette, and stood smoking for a while. When she turned to look up, I ducked behind the curtain.

*

Over the next few weeks, I would check my appointment book regularly to see if she had requested a second session. I was tempted to call her mother, but didn’t.

Then one day, there it was: an appointment for the following Friday. And another for the week after, and the week after that, on and on as far as June.

On each subsequent visit, Dorota would nibble on a croissant (which she never finished) and sip from a cup of coffee (likewise) while we discussed the events of her life. By 45 minutes she would be glancing anxiously at the clock. By 50 minutes she’d be gone.

What did I learn about her childhood? She loved Scooby Doo, but would stop watching before they unmasked the villain. She devoured comic strips, but never looked at the last frame. She loved the songs her parents played on the car stereo but would put her fingers in her ears as each faded.

A curious, intelligent girl, she earned good grades at school despite never reading books in their entirety, and her essays containing no conclusions. Her small group of friends got used to her hanging up on them mid-phone call, or walking off on them mid-conversation.

Sunday evenings, sunsets, and the last days of the holidays depressed her.

‘Do you have a job?’ I asked her.

‘I’ve had several. They never last long.’

‘Is there a career you’d like to pursue?’

She thought about it.

‘Maybe explorer. But everywhere’s been discovered.’

On her fourth visit, we discussed her love life.

Dorota’s first date, aged fifteen, had started well (the boy found her charming). She had promised her parents to be home by ten, and at nine-thirty started gasping for breath, her face turning red. When the boy asked what was wrong, she panicked and fled.

The few dates that followed ended similarly.

When she was eighteen, Dorota moved to Berne to study for a philosophy degree. One night, in the absence of parental deadlines, she followed a law student back to his studio. The act of love-making, however, proved a torment. As her partner’s moans rose in intensity, and as her own climax neared, her anxiety grew. ‘Stop,’ she pleaded, pushing him off. That first time, he was understanding, but when it happened again, and then again, he dropped her. From then on, Agathe’s sex life had been solitary bar the occasional, unsatisfactory coupling.

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ I said.

‘Hmm,’ said Dorota.

She took a bite of her croissant, crossed her legs and brushed her hair out of her eyes. I had lost my train of thought.

‘Let’s stop there for today,’ I said. She raised her eyebrows, pursed her lips, then stood up.

‘If you say so,’ she said.

I hid behind the curtain, watching her go. She set off along the road, pulling a beret over her head, a skip in her stride. I stared after her until she disappeared.

*

‘But what can it mean, doctor?’

‘Hmm?’

‘These dreams. This desire to be ravished by badgers.’

‘Sounds perfectly normal, Mrs Stückli.’

‘Don’t talk nonsense. And my name’s Rückli.’

My work was suffering. All I could think about was Dorota, her endophobia (a term of my own invention) and her sad, solitary lovemaking.

Something had to be done.

*

Dorota’s sixth visit was also her last. She arrived in a light, summer dress, looking radiant and more beautiful than ever. She swung her legs up onto the couch.

‘What do you know about Tantric sex?’ she asked.

‘Tantric sex?’

‘Mmm. I’ve been reading an article about it.’

She kicked off her shoes and wiggled her toes. I stared at them.

I knew next to nothing about Tantric sex.

‘I know a great deal about Tantric sex,’ I said. ‘If you’re curious about Tantric sex, you’ve come to the right guy.’

She flashed a broad grin at me. ‘I knew it!’

I racked my brains.

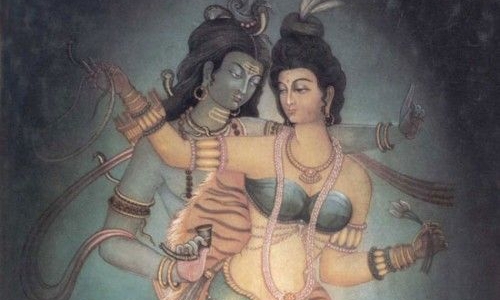

‘It’s an ancient Hindhu practice,’ I said, ‘with its roots in the, ah, Pravapura dynasty. By slowing down their movements, aligning their breathing and adopting the right positions, Tantric devotees can prolong their erotic pleasure almost indefinitely.’

‘So it never ends?’ asked Dorota.

‘You could say that,’ I said.

‘Will you teach me?’

I looked at the floor, as if the answer to her question might reveal itself on the rug.

‘If it would help,’ I said, ‘I am prepared to instruct you in Tantric technique.’

‘Yes please,’ said Dorota.

She looked at me hopefully.

‘In that case,’ I said, ‘we can start tomorrow.’

‘If it’s convenient’, said Dorota, ‘you could come to my place.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘That does sound convenient.’

*

At six the next evening, I walked across town to Dorota’s apartment. Having spent the day reading up on Tantric maneouvres, I felt reasonably equipped. The important thing in these cases is… I’ll rephrase that… the important thing in life is to project a reassuring air of authority.

She lived in a Hausmannien lakefront building. I found her name on the mailbox – top floor. In the lift going up, I hummed the Ride of the Valkyries.

I knocked softly on the door. Dorota ushered me into a dimly lit, ornately furnished apartment. I slipped off my shoes. She was wearing a skimpy, black, silk camisole. Her toenails were red.

‘You look, ah…’ I said, while she put her hand round my neck and slipped her tongue past my lips.

‘Come with me,’ she muttered.

Her bedroom contained a red bedspread, black pillows, and a large oil painting of a naked woman who resembled Dorota. Books were scattered on the floor. Candles flickered. I smelt incense.

‘Would you like to get undressed?’ she asked.

‘Good idea,’ I said.

‘I’ll be back in a minute,’ she said. ‘Would it be OK if Oscar watched?’

Oscar? She’d never mentioned an Oscar.

‘He’s my cat,’ she said.

‘Why not, then,’ I said. ‘He’ll keep himself to himself?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Dorota.

She exited. I unbuckled my belt, slipped out of my trousers, and took off my jacket and shirt. Standing there in my underwear, I contemplated the oil painting. The life-sized naked woman resembling Dorota stood before a flaming volcano, her right hand cupping her left breast.

‘You settling in?’ asked Dorota. A Siamese cat lay curled in her arms, acquiescent as she stroked its chin. She put the cat down on her dressing table. I studied it.

‘That cat…’ I said.

‘Hmm?’

‘It’s stuffed.’

‘Sorry?’

‘It’s not alive. It’s a dead cat. It’s a stuffed, dead cat.’

‘How dare you,’ said Dorota.

‘Now hang on,’ I said, conscious of the erotic charge dissipating by the moment, ‘I’m not making any sort of judgement. I just couldn’t help noticing it.’

‘You couldn’t help yourself,’ she agreed. ‘You disgust me.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Get out.’

I looked at the stuffed cat, the naked woman in the portrait, then Dorota.

‘OK,’ I said.

*